Rithika Merchant featured in Colossal

Through Mystical Mixed-Media Narratives, Artist Rithika Merchant Explores Intrinsic Connection

November 9, 2022, by Grace Ebert

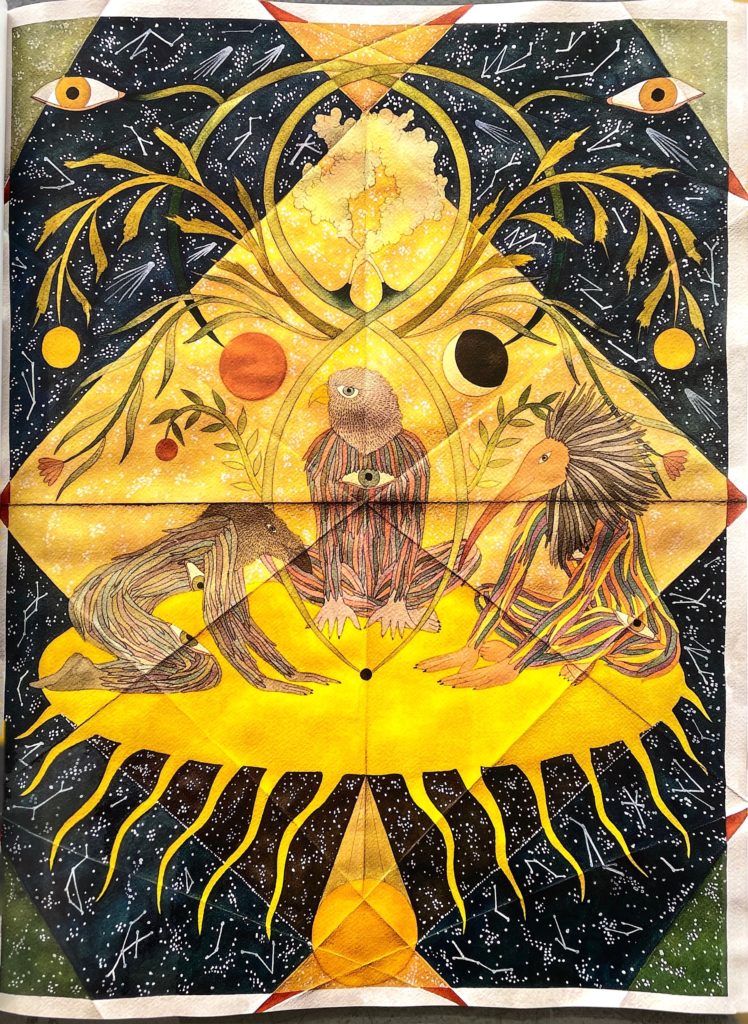

“The Inner Sanctum” (2022), gouache, watercolor, and ink on paper, 100 x 70 centimeters All images © Rithika Merchant, courtesy of Galerie LJ, shared with permission

“I’m drawn to works that are rich in symbolism and also have a strong element of storytelling,” says Rithika Merchant. “I love seeing the artist’s hand in the work—I have a huge appreciation for small details and works that draw from a multitude of references—literary, mythical, and visual.”

The Mumbai-born artist manifests these same qualities in her practice, creating works that expertly translate concepts and themes through her own idiosyncratic allusions. Beginning with hours of study, research, and reading on an eclectic array of topics, Merchant tends to hone in on an image that she sketches onto sheets of paper, sometimes folded into generous rectangles or triangles. She then paints in gouache and subtle, muted washes of watercolor, layering translucent pigments atop inked renderings of landscapes, mythical hybrid creatures, and patterns of foliage.

While Merchant’s influences are broad—they range from the specific like 17th-century botanical drawings, Kalamkari prints, Mughal paintings, and Kalighat folk art to the general like religious iconography and narrative tapestries—they emerge as a distinct visual lexicon. The artist often gravitates toward symbols that transcend cultural or geographical boundaries, choosing to incorporate human anatomy, celestial objects, and botanical elements. Although universal, these images are married to language in Merchant’s mind and in service of an individual narrative. “I also have a notebook in which I make lots of written notes and diagrams, but I almost never make sketches or studies of things. I sketch more with words than images,” the artist shares.

“Bennu and Futuraheliopolis” (2021), gouache, watercolor, and ink on paper, 100 x 70 centimeters

Evoking the spiritual side of Hilma af Klint and the strange characters of Leonora Carrington, the resulting works are cartographic and chart-like, mapping surreal renderings of feathered wings, cycloptic figures, or a troupe of dancing creatures onto a plane intersected with creases and enclosed by a thin frame. Texture pervades each of the works through mixed mediums, collaged details, and patterns comprised of minuscule dots and lines.

Whether collaged or drawn on paper, each piece illuminates the intrinsic connections between the mind, body, and Earth. “I think there is something powerful in taking whatever scraps you can find and putting them together to create something meaningful,” she says.

Merchant is currently in a residence in Saint-Louis, Senegal, and will release her first monograph titled The Eye, The Sky, The Altar next month. For a glimpse into her studio and process, visit her Instagram.

“Seed Vault” (2022), gouache, watercolor, and ink on paper, 100 x 70 centimeters

“Midnight Sun” (2022), gouache, watercolor, and ink on paper, 100 x 70 centimeters

“Festival of the Phoenix Sun” (2022), mixed-media collage with gouache, watercolor, ink, and magazine cutouts on paper, 140 x 100 centimeters

“Altered Destiny” (2022), gouache, watercolor, and ink on paper, 100 x 70 centimeters